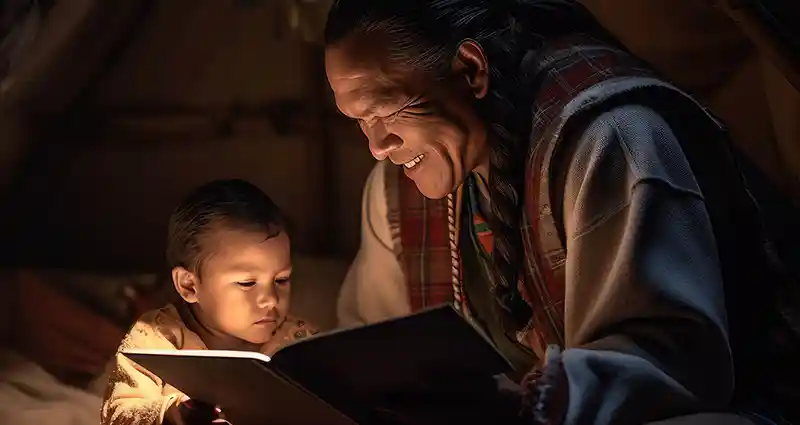

Languages 4® Generations | Indigenous Ancestors

Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it (Chief Joseph) of the Nez Perce: A Leader for His People, An Example for All

Chief Joseph, half-length portrait, seated, facing slightly left, wearing headdress. (De Lancey, 1900)

March 6th, 2025

Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it (Chief Joseph) of the Nez Perce: A Leader for His People, An Example for All

Chief Joseph, known in his language as Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it ("Thunder Traveling to Loftier Heights"), stands as one of the most influencial voices against the systematic erasure of Indigenous sovereignty. A leader of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce, he was a strategist in war and an uncompromising diplomat in peace. His name is etched in the annals of history for his resistance during the Nez Perce War of 1877 and his tireless advocacy for his people's dignity and rights in the face of U.S. government betrayal.

"The earth, my mother and nurse, is too sacred to be valued or sold for gold, and my bands have suffered wrong" (Chief Joseph, qt. in Warren 278).

The Legacy of His Father: A Land Promised, A Land Betrayed

Joseph was born around 1840 in the Wallowa Valley, a land of winding rivers, rolling hills, and an ecosystem that has sustained the Nez Perce for countless generations. His father, Old Joseph (Tuekakas), had embraced peace and sought to protect their homeland through diplomacy. He once stood in solemn agreement, trusting the promises made by American officials that the Wallowa Valley would be Nez Perce land "always" (Jain 122).

But promises written in ink could not withstand the tides of greed.

In 1863, the U.S. government, eager to open the region to settlers, forced a new treaty that shrank the Nez Perce reservation to a fraction of its original size. Many bands, including Joseph's, never agreed to this so-called "Steal Treaty" (West 9). As his father lay dying, he imparted words that would become the foundation of Joseph's leadership:

"My father held my hand, and he died. Dying, said: 'Think always of your country. Your father has never sold your country. Has never touched white man's money that they should say they have bought the land you now stand on. You must never sell the bones of your fathers'" (Warren 276).

With these words, Joseph inherited the chieftaincy and the responsibility of resistance.

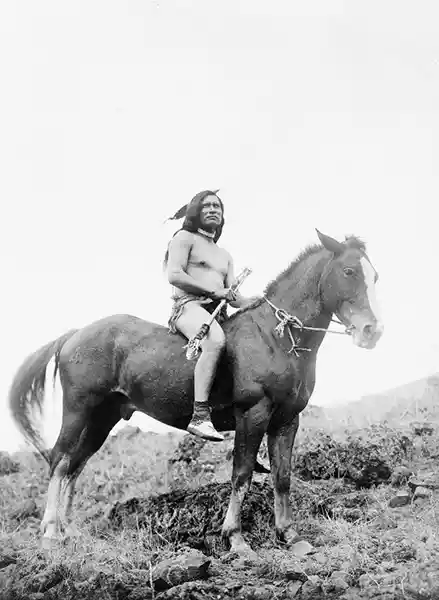

A Nez Percé man on horseback (Curtis, 1905)

The 1877 War: A Betrayal, A Fight for Survival

By 1877, the U.S. government issued an ultimatum: Joseph and his people had 30 days to abandon their homeland and move onto the designated reservation (Wells 35). He prepared to comply with deep reluctance, understanding that armed resistance would only bring devastation. However, before the departure could take place, a small group of Nez Perce warriors, enraged by past injustices, killed white settlers. The U.S. Army seized upon the incident as a pretext for war. What followed was one of the most extraordinary military campaigns in American history.

Though often falsely mythologized as a "Red Napoleon," Chief Joseph was not a war chief in the traditional sense. His role was that of a protector, a negotiator, and a strategist in ensuring the survival of his people. Under the leadership of Looking Glass, White Bird, and other war chiefs, the Nez Perce embarked on a 1,100-mile retreat through the Rocky Mountains, outmaneuvering and defeating the U.S. Army in multiple engagements (Wells 36).

The Nez Perce sought sanctuary with the Crow, a neighboring tribe with longstanding trade and diplomatic ties. As they fled the relentless pursuit of the U.S. Army, they hoped to find refuge in Crow territory, located in present-day Montana and Wyoming. However, due to their own challenges and political pressures, the Crow were unable to offer the assistance the Nez Perce had hoped for. With no other options, the Nez Perce turned toward Canada, aiming to reach Sitting Bull and the Lakota. Just 40 miles from the border, they were ultimately surrounded in the Bear Paw Mountains.

There, after a five-day siege, Chief Joseph delivered the words that would be immortalized:

"The earth, my mother and nurse, is too sacred to be valued or sold for gold, and my bands have suffered wrong" (Chief Joseph, qt. in Warren 278).

The Aftermath: Exile, Diplomacy, and Betrayal

Despite the surrender, Joseph believed he had negotiated safe passage for his people back to their homeland. Instead, they were sent to disease-ridden camps in Kansas and then to Oklahoma, where nearly a quarter of their people perished. In 1878, the U.S. Indian Commission noted that Joseph's people had suffered immensely, stating:

"The bad effects of their location were manifested in the prostration at once of two hundred and sixty of them; and in a few months in the death of a quarter of the entire number" (Report of the Indian Commission, qtd. in Warren 302).

Joseph, however, did not resign to despair. His war shifted from the battlefield to the halls of Washington, D.C. He lobbied Congress, met with President Rutherford B. Hayes, and delivered speeches that shook the nation's conscience. He articulated the Nez Perce case not just as a grievance but as a profound indictment of U.S. policy:

""When I think of our condition my heart is heavy. I see men of my race treated as outlaws and driven from country to country... We only ask an even chance to live as other men live. Let me be a free man—free to travel, free to stop, free to work... free to think and talk and act for myself—and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty" (Chief Joseph, qtd. in Warren 305).

His words stirred sympathy but did not move policymakers to justice. Though some Nez Perce were eventually allowed to return to the Northwest, Joseph and his followers were denied access to their Wallowa homeland. Instead, they were relocated to the Colville Reservation in Washington, among tribes with no ancestral ties (West 6).

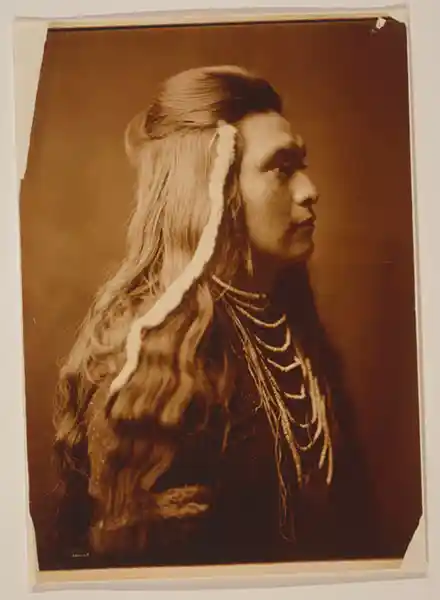

The Last Fight: A Man Exiled from His Land

Joseph never stopped advocating for his people's return to Wallowa. He traveled east again in 1903 to plead his case, but the government remained indifferent (West 10). When he died in 1904, the reservation doctor recorded his cause of death as "a broken heart" (Warren 310). Yet his spirit never surrendered.

His resistance was not only one of survival but also of sovereignty. He understood the tactics of the U.S. government—how they used treaties as weapons, wielded false promises to justify displacement, and undermined Indigenous sovereignty through legal manipulations.

In many ways, Chief Joseph's fight did not end with his death. His descendants and the Nez Perce people continue reclaiming their rights, stories, and land. The struggle for Indigenous sovereignty over language, culture, and land remains, echoing the words of their ancestor, who refused to accept the erasure of his people.

I claim a right to live on my land, and accord you the privilege to return to yours" (Chief Joseph, qtd. in Warren 306)

Today, Chief Joseph's legacy is recorded in the history books and in the voices of those who continue to fight for Indigenous sovereignty. He remains a towering figure—a reminder that the fight for justice is never in vain, no matter how long.

Head-and-shoulders portrait profile of Nez Percé man. (Curtis, 1905)

References:

Jain, Samvit. Leader and Spokesman for a People in Exile: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce. The History Teacher, Society for History Education, 2009, pp. 121–139.

Warren, Robert Penn, and R.P.W. "Chief Joseph of The Nez Perce." The Georgia Review, vol. 36, no. 2, 1982, pp. 269–313. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41399718.

Wells, Merle W. The Nez Perce and Their War. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, University of Washington, 1964, pp. 35–37.

West, Elliott. The Nez Perce and Their Trials: Rethinking America's Indian Wars. Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Montana Historical Society, 2010, pp. 3–18, 92–93.

Chief Joseph: A Symbol of Resilience. https://www.redwoodleader.com/post/chief-joseph-a-symbol-of-resilience

Connect With Us

Follow our journey, share your thoughts, and participate in the conversation. Let's keep languages vibrant together.

Languages 4™ is more than a tool; it's a partner in the mission of preserving and revitalizing Indigenous languages. We invite reach out to us explore how our platform can support your language teaching goals. [Join the Conversation 📩 Subscribe to our Newsletter ] and take a step towards sustaining the rich heritage of Indigenous languages.

Tim O'Hagan

Founder and President, Languages 4®

Ready to embark on this transformative linguistic journey? Dive in and experience the confluence of tradition and innovation as we reimagine the future of Indigenous language learning.

[Join the Conversation to Subscribe to our Newsletter ]